Over the years Clidive has explored many remote diving locations, particularly in Scotland. We find the effort these trips require in terms of logistics, management and expertise are well worth the reward of visiting rarely-dived sites in often stunning visibility. I consider these trips to be the jewel in the crown of Clidive trips.

This year, Debbie organised an expedition to Barra. Barra is the southernmost island of the Outer Hebrides with any substantial population on it. We chose this as it gives us access to the mostly uninhabited islands to the south and we were hoping to be able to dive at the very south of the island chain at Barra Head. The islands sit on a ‘shelf’ that plunges to 150m and we were also hoping for clear Atlantic visibility, untouched dive sites and dramatic scenery. I think it’s fair to say we were not disappointed.

For more photos of our trip, have a look here: https://photos.app.goo.gl/9ZAjDyiGnUGEomTHA

Day 1-3 – staying local

For the first three days we were hit with fairly strong (up to force 5) winds from the south-west. This would be too strong to dive in directly, but the nature of islands is that there is always somewhere to dive that is sheltered from the wind. In that vein, for the first three days we dived some more sheltered sites – two pinnacles on the eastern edge of the shelf, a pinnacle on the plateau between the islands, two wrecks and a drift dive.

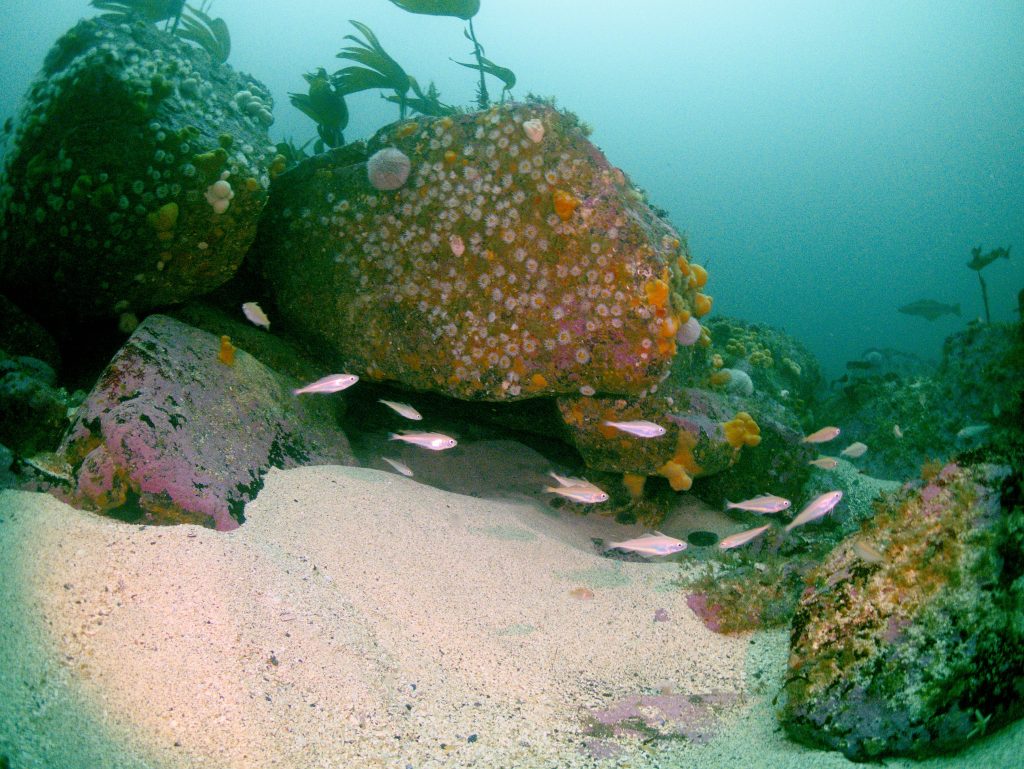

The pinnacles were in about 25m, with superb visibility and lots of gullies. The walls were festooned with life – dead men’s fingers, jewel anemones, crabs, langoustines, starfish, wrasse and many shades and types of soft corals and sponges. At the bottom of the gullies we found pure white sand with huge shoals of sand eels swimming over it and scallops, crabs and starfish living in it.

As our bottom time approached we usually came up more gentle, but equally fecund slopes and into a swaying world of kelp inhabited by more soft corals and featherstars. We spent our safety stops watching jellyfish undulating.

The first wreck we dived was the Seniority – a WW2 cargo steamer, lost without loss of life in 1950. It is broken up, absolutely teeming with life and with excellent visibility. Much of it is sitting on a bed of maerl – a beautiful purple hard coral. We were easily able to penetrate parts of the wreck and explore it as fully as our bottom time allowed.

There were many easily identifiable parts – a propshaft, two large boilers, a davit, bollards, chains, pieces of hull; and there was a lot that was more mysterious – machinery, long tubes leading nowhere, tangles of metal. It was an extremely scenic dive. One for both die-hard wreck lovers and for those who enjoy lots of life.

The wreck was home to crustaceans, large shoals of wrasse, anemones, the aforementioned maerl and much much more. A wreck for all tastes, and more than one dive can fully reveal. On our first dive here the majority of the divers stuck to the pinnacle the wreck settled on, only Ben and myself spotted the 2,876 tonne ship lying there in all its glory. The rest of the group decided to dive again with the shot right on the wreck to verify that Ben and I were not in fact cooking up a story and there was a massive shipwreck there after all!

For the drift we headed to the sound of Sandray that separates Barra/Vatersay from the next large island south.The various sounds in the Outer Hebrides have fast currents due to the large flow of water being funnelled through them, so we decided to use that to our advantage.

The dive was in 20-25m and was over a sandy bottom with a lot of life on it and isolated rocky outcrops with even more life on them. As we whizzed by at a healthy – though not excessive – rate, we saw a lot of crabs, some flatfish, anemones, kelp, and much more. I even saw an octopus – though once again there were doubts from others, even my buddy, who couldn’t get back against the current to see it!

The first three days, particularly day 3 were not in ideal conditions, but we managed some fantastic dives, which would rate as top dives on most other dive trips. Happy as we were, we were looking forward to venturing further south over the next few days as the winds dropped.

Day 4-5 exploring further south

The weather was still not ideal, but the worst had passed so we headed south and did two days of diving in the large sounds further south – the sound of Pabbay and the sound of Mingulay. This involved some heroic boat driving from Ian and Michael, but we were able to plan dives in the lee of the wind.

The dives in these sounds made it clear we were diving on high-energy sites. They were steep walls, again in about 25m, generally with a lot of boulders at the bottom and leading onto pure white sand. The visibility was, if anything, even better than on the east as we were more exposed to the Atlantic here.

They were very colourful dives, with a wide selection of soft corals, hydroids, crustaceans, wrasse and the like, along with large schools of cod-family fish and sand eels. There was a lot to explore, with life filling every nook and cranny of the rocks. I particularly enjoyed diving where the boulders met the sand and you could watch the larger fish chasing the sand eels on one side and the reef life on the other.

We usually ended the dives shallowing into life-filled kelp before bagging up. It was clear that a lot of current comes through here and life was making the most of it.

It was on one of these dives I saw something that I’d never seen before, and no-one on the boat had in the UK either – a tuna! It shot past so I really only got a look at its aft and distinctive tail, but it was large (I initially thought it was a big seal). These were stunning dives that I’ll remember for a long time.

We also managed a particularly memorable lunch on day 5. We had planned to stop in a bay with several beaches. We are used to stopping on deserted shores, but we were aghast to find all but one of the beaches absolutely full… of seals! The colony must have been several hundred strong, and many of them swam excitedly to see us, some of them leaping in and out of the water almost like dolphins! We went to the smallest beach and had our lunch while the seals bobbed in the water, watching us closely. One or two got a bit closer to have a look at the boat, but most stayed a good distance off, just to keep an eye.

After lunch we dived on the other side of the Sound of Mingulay at a small set of islets called Outer Heisker.

Days 4 and 5 were stunning, but we knew that on day 6 the wind was finally dropping and we had a chance to get down to the very south to Barra Head. We had had a great day, the life was even more prolific the further south we went. Would we get there and what would it be like?

Day 6

We awoke to flat seas and calm winds. We knew this could bring fantastic diving. And midges. The only downside was the fog. It was pretty thick, and we were concerned about how safe it would be to dive. As we got ready the fog seemed to lift somewhat, so we set off, aiming for Berneray – the southernmost island in the Outer Hebrides and Barra Head – our goal for the trip.

As we headed south the fog came and went and by the time we got to Berneray it was pretty thick. We decided to have a look round and see if we could find somewhere safe to dive. We found an inlet next to Barra Head where we could avoid heading out to sea in the fog. It also had a pretty shear wall down to about 25m. We kitted up and jumped in.

On the bottom we found a world of large boulders and tons of fishlife. The exposed nature of the site meant it was often quite scoured, and looked very dramatic. There were atmospheric gullies between the boulders and as we dived inland there was more in the way of soft-coral. Despite days of strong southerly winds blowing right up this gully, the clear Atlantic water and the rocky/sandy bottom meant that the water was crystal clear.

When we finally ascended, pretty much at the end of the inlet (still in 20m) we could see the drama of the site before us, the steep walls, the boulders, the chasms. Personally I love these dramatic rock-scapes, and while we’d had a good amount of it earlier in the week, this was the dive of the trip for me.

While we waited for other divers to come up we watched a family of dolphins – two adults and a baby – swimming just outside the inlet, then we headed round to the north of the island for lunch on a “pontoon”. Not that we found any pontoon, but we had a bijoux little beach all to ourselves, which was lovely.

For our final dive we headed to the east of the island and dived off a rock called Sgeir Mhor. There was a bit of current, but when we tucked in it was an enjoyable high-energy site with a lot of life, rocks and gullies housing soft coral, hydroids, crustaceans and schools of wrasse. At the end of the dive, Ben and I kept close into the rock and ascended in not a great deal of current. The other two pairs of divers were picked up by the current on ascent though, and the boat followed them out into the mists. It took a while of looking for us to realise that we’d not drifted off and were only a few hundred metres from where we’d started!

Diving on Barra – and expeditionary diving

We had six wonderful days of diving in a part of the world that is rarely dived. We managed to do great dives in all the weather threw at us and came back to base smiling every day.

It was a lot of effort for Debbie to organise this trip, it was a lot of effort to get there and back – multiple days of driving, and/or trains and/or planes; we had to experiment with tides, go out and see if things looked like the charts and spend hours pumping our own cylinders.

But this is the only way to see sites like this. There are no commercial dive operations out there, no guide books, no skippers to point the way. It’s an adventure, it’s a team effort and it’s an amazing way to spend a week of your time.

Clidive aims to organise multiple expeditions every year, some to more unknown places such as this, some to places we know a little better. These are opportunities to dive sites that other divers rarely get to see and are the best diving we do. If you’ve not been on an expedition with us this year you should be working out how to do it next year. You need to be a Sports Diver or equivalent, be comfortable in a dry suit and have done a good number of dives in different conditions. Next year it could be you seeing all these amazing things.

We are an LGBTQIA+ friendly club

We are an LGBTQIA+ friendly club