by Peter Martin

Lanzarote rose out of the Atlantic around 15 million years ago. It is now a volcanic desert in the middle of the ocean, a black lava rock speckled with white clusters of houses and tourist apartment blocks. And its coastal waters provide good diving, as twenty-two Clidivers found when they visited the island on a training trip in March 2015. Five instructors and two assistant instructors, led by the indefatigable dive manager Gillian, were aiming to help twelve trainee divers to complete the open water dives needed to gain their ocean or sports diver qualifications. Three other club members came along for fun diving and snorkelling. At this time of year, the average temperature is around 19 ºC, and divers can enjoy 18 ºC waters. We stayed on the South coast, in the little town of Puerto del Carmen.

Days Minus One and Zero: A mighty sneeze

A few of us arrived early and decided to explore the volcanic desert created by massive eruptions in the 1730s. We wandered among bizarre lava formations, had lunch in a collapsed lava tube, and marvelled at the evidence of how close the earth’s heat is to the surface: At Timanfaya National Park, a ranger poured water into a hole in the ground. For a few seconds, nothing appeared to happen. Then the hole erupted and the water, now boiling and steaming, shot back out with a mighty sneeze. It wasn’t quite Yellowstone’s Old Faithful geyser, but pretty impressive nonetheless.

Day One: Fearless fish, minor mishaps, and angel tales

Safari Diving, our diving base, is situated directly by a little beach. Two lines of volcanic rocks stick out of the water and form a pair of natural breakwaters, thus making a little pool that is protected from ocean currents. Beyond this pool, the sea floor gently slopes down to 20 m depth, in visibility never worse than 10 m, and often better. It’s an ideal spot for training dives.

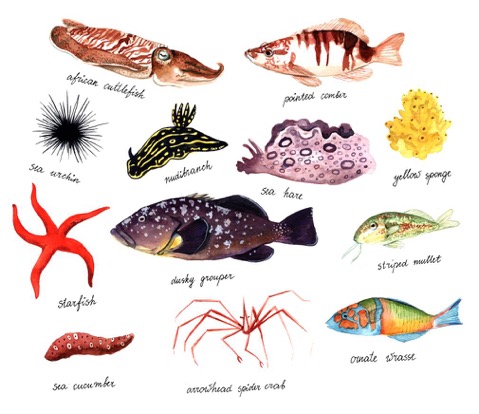

First up for all trainees was a shore dive. Each instructor taking a group of two or three to test the waters and the trainees’ skills. One of the first things we noticed underwater was how intrepid the fish were. Breams and wrasses swam right in front of our masks. Mullets were often behind us, looking for a diver’s fin to stir up some sand and expose the food that hides within. The cuttlefish were a little more wary, but they, too, kept their cool and didn’t waste any ink.

Day One also decided to test our mettle with a series of mishaps. Masks, taken off during rescue exercises, got swept away (but were found again). Equipment left on the beach between dives got snatched up by the rising tide (but was recovered, at the expense of a wet drysuit). A leaky hose meant that an instructor’s air supply depleted rather quickly, so that one dive had to be ended prematurely. A sports diver trainee’s BCD hose broke completely while underwater; he was able to continue the dive, controlling buoyancy with his breath. However, the prize for most original mishap must go to the diver who lost a tooth crown on the sea floor. This was not found again, at least not by us. Fortunately, after the dive, an emergency dentistry appointment yielded a speedy replacement.

Anne, who had gone boat diving with a group led by one of the guides from Safari Diving, returned with tales of angel sharks and stingrays, to everyone’s delight (and possibly a little envy).

Day Two: An hallucinogenic wreck, an alien blob, and stars in the sea

On Day Two, we had a wreck to dive and distance lines to fix. The wreck, a former fishing boat sunken in the old harbour area to provide a place of interest for divers, was well preserved and lay at an oblique angle at 15m depth. A trumpetfish swam around old frayed ropes and rusty railings, and colourful nudibranch sea slugs crawled on sponges in the sand below. The wreck itself provided a surreal experience for some. One ocean diver compared it to a drug-induced dream of weightless flight over a world whose angles were all wrong. That’s one way to know that you’ve started to get the hang of buoyancy.

At dusk that day, we met for what turned out to be one of the highlights of the trip: a dive at night in the shallow waters of a small harbour. The instructors did a fantastic job of organizing the group in a caterpillar formation, alternating instructors with buddy pairs of sports and ocean diver trainee. As so often, the coastal shallows turned out to be a party venue for nocturnal sea creatures. The sea cucumbers had come out to play, spider crabs ogled us with their pincers in fighting position, an octopus fled before our lights. Eventually, we came across an alien grey blob, larger than a man’s fist, its body covered by misshapen protuberances. As we later found out, it was a sea hare – a gastropod mollusc and thus a close relative of the nudibranchs, albeit one not blessed with a pretty appearance. Toward the end of the dive, we all gathered together and put our torches in the sand. After 30 seconds of near complete darkness, faint stars began to appear before our eyes, blinking on and off like faint musical notes. Planktonic bioluminescence – even if we had seen nothing else, it would have made the night dive worthwhile.

Day Three: Taking responsibility, a garden of eels, and a lot of stamps

The morning of Day Three was dedicated to the final training dives. The instructors were busy making sure that all trainees had a chance to demonstrate the remaining skills needed for their qualifications. Everyone did!

The last dive was for fun. For many, it was the first time that they were diving in a buddy pair without direct supervision by an instructor or dive guide (although instructors discreetly stayed in the vicinity of the newly qualified ocean divers). Encounters included a portly grouper, several frilly nudibranchs, and a happy pair of cuttlefish swimming side by side. Maybe the most astonishing sight were the garden eels, who live with most of their bodies hidden inside their burrows in the sand. Only their heads stick out, like fat blades of grass. Hundreds of eels lived side by side in a convivial field. As we swam close, one by one they gradually retreated into their sandy lairs, and disappeared out of sight when we floated over their homes.

In the afternoon, everyone congregated in our apartment complex and gathered around Gillian and the other instructors. Dives were signed off and qualifications awarded. Everyone had passed, and got their qualification pages signed and stamped.

Day Four: Everyone wants more diving, and How to avoid the incident pit

The final morning saw our divers reflect on a great trip. New friendships had been made, and plans for future dive trips were being hatched. We also talked about our mishaps, and how the unforeseen problems had been good learning experiences. Not least, many a diver realised that an underwater problem doesn’t need to spell disaster, when it is addressed straight away and with a calm mind.

Before we said our good-byes, I asked the trainees “what should definitely be in the trip report”. The most frequently mentioned point was how impressed we were by the generosity of the instructors, who gave their time and effort to teach us to dive and answer our novice questions; after all, they may well have been excused for wanting to hop on a boat and explore what else there was to see in Lanzarote’s waters. A big thanks, therefore, to assistant instructors Preeda and Ian, and to instructors Natasha, Don, John, and Phil. Our special gratitude goes to Gillian, instructor and dive manager extraordinaire, whose exceptional organization was the boat that kept us all afloat, and from which we could dive into Lanzarote’s waters to marvel at the wonders therein.

We are an LGBTQIA+ friendly club

We are an LGBTQIA+ friendly club