By Elaine Hendry

In December last year, towards the end of a trip to Mozambique, Nick and I tore ourselves away from watching hippos in a watering hole to sign up for Clidive’s trip to St Kilda. It required no discussion – Scotland is my favourite diving destination in the world and a rare opportunity to visit its most westerly point for the first time was too good to miss.

What, where and why is St Kilda?

First off (and with thanks to Wikipedia), a few quick facts about St Kilda – or Hiort, as it’s known in Gaelic.

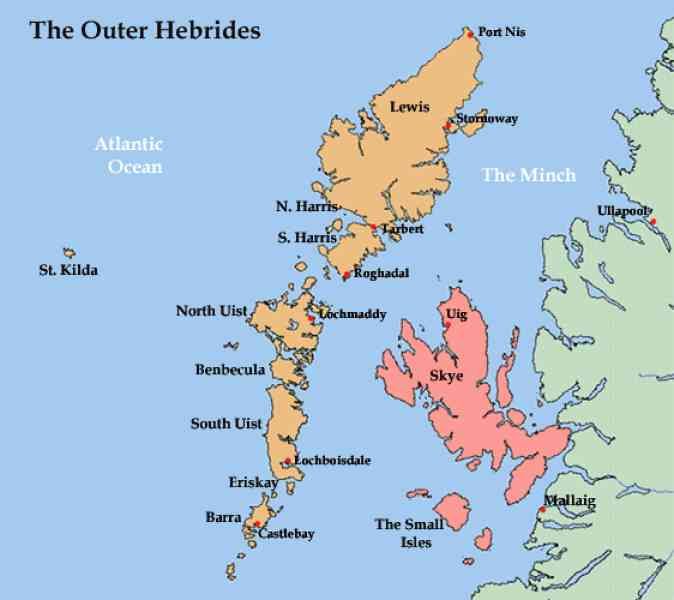

St Kilda is an archipelago that is officially part of the Outer Hebrides. However, situated way out in the North Atlantic, 40 miles/64 km west-northwest of its nearest neighbour, it’s not exactly a close part of the family.

It comprises four islands: Hirta, which has the highest sea cliffs in the UK, Dùn, Soay and Boreray – the remnants of a long-extinct ring volcano that rise from a 40m-deep plateau.

St Kilda is known to have been permanently inhabited for over 2,000 years, although who knows why! Due to the unpredictable weather and rough seas, the inhabitants relied not on fish but on the bird population for food – both the eggs and the young birds. The size of the (human) population rose and fell over the centuries and eventually dropped to 36 in May 1930, when everybody was evacuated due to the upheavals of WW1 and illnesses introduced by tourism.

The archipelago is now owned by the National Trust for Scotland and is one of Scotland’s six World Heritage Sites.

It is home to: a small military base; seasonal volunteers restoring the buildings; two breeds of sheep that date back to the neolithic and iron age periods; unique subspecies of wren and field mouse; over 1,400 equally unique stone storage structures known as cleits; and thousands of gannets, puffins and northern fulmars.

Finally, in case you’re wondering who St Kilda was, they never existed! There are various theories for the origin of the name, including that it comes from the Norse words for a well (kelda) or a shield (skildir).

Five top tips for a dive trip to St Kilda

1. To avoid disappointment, assume you won’t get there

It’s a six-hour motor to St Kilda from the western end of the Sound of Harris, so you need at least a couple of days of favourable conditions to get there, do 2/3 dives and get back; longer if you want to go ashore to explore.

Wind is a problem, but the Atlantic swell is an even bigger one, so even if the wind abates for a while, your boat might not make it. Tales abound of divers who’ve signed up for several trips but have never actually made it.

2. Embrace the Hebrides!

Even if you do make it, you might only get three or four dives round St Kilda itself. The rest of the week will be spent cruising Skye, the Outer Hebrides and the coast of the mainland. This is a wonderful experience in itself and should be enjoyed to the maximum. Clidive loves to dive Scotland, but only on a liveaboard can you cover the distances that we did in our week.

3. Adjust your expectations of ‘liveaboard’

If the term conjures up fluffy warm towels, copious meals and more crew than divers – i.e. the soulless gin palaces of Egypt and other exotic locations – you need to delete that picture immediately. The only thing they have in common with a UK liveaboard is an engine and an ability to float.

Once a fairly common part of any UK dive club’s dive programme, the 10 or so remaining UK liveaboards that operate mainly around Scotland and Norway are tough, no nonsense vessels that offer an experience more akin to a floating youth hostel than a floating hotel.

MV Claeson, skippered by the highly respected Bob Halton, is a larger-than-normal, steel-hulled trawler built ‘to withstand the worst of the weather’ and unusual in in the amount of diving deck space it offers.

12 of us slept in six windowless, twin-bunked cabins below decks. While this might not suit everybody, I have to say that the complete darkness combined with the gentle rocking of the boat gave me the best nights’ sleep I’ve had in many a year!

Three heads (marine-talk for loos!) with hot showers, were located by the diving deck and a at the other end of the boat. Even the two nearest to the cabins required climbing up to the deck, opening a heavy iron door and dashing across the deck for that 2am pee.

An indoor kitting-up area offered shelter, a bit of warmth and a place to hang drysuits. It also housed the washing machine and the far-more-important tumble dryer – drysuits appear to be even more prone to leaks once the water temperature drops below 12C!

The dining area just about seated all 12 of us and offered the luxury of a permanently steaming hot water urn. The food was tasty, filling and pretty health and – amazingly – catered on this trip for more than the usual dietary needs.

The young crew comprised: Tash, combining chef and general boat-hand duties – including plying us with hot chocolate and marshmallows as we emerged from each dive – with an interesting marine research project; and Tom, who helped with kitting up as needed, counted us out and back in, and operated the sturdy diver lift.

4. Be prepared for the cold

The water temperature anywhere in Scotland is generally 9–11C and the air temperature in the far North West, particularly when you’re at sea, isn’t much higher, even in June and when the sun is shining.

The first few days of our trip coincided with unseasonal northerly winds bringing icy blasts from the Arctic. Struck by the cold as she landed at Inverness, Fiona invested in an extra padded jacket before she boarded the boat – and she’s a full-blooded Scot!

5. Listen carefully to the briefing, then study the charts and then ask for more information still

This is very different territory to Plymouth, Portland and even Pembrokeshire – this is full-on adventurous diving territory. Even seasoned skipper Bob didn’t always know when, where and in what direction local currents would be running, particularly the sort that pick you up as you hit 25m and drag you out to sea [see below].

Similarly, those charming drawings of underwater clefts in cliffs rarely translate into a straightforward navigation exercise once below the surface. Having a detailed understanding of the site, a good sense of the overall topography and a proper discussion with your buddy/ies before you leap in makes a lot of sense. I wish I’d done that [see below]!

So what of the trip?

We picked up the boat at the small fishing harbour of Gairloch and had an enjoyable first dive just outside, at Longa Island. Prawns, scallops, shoals of small saithe, the biggest crab I’ve ever seen AND an octopus – not bad for a shake-down dive. By the early afternoon, we’d crossed the Minch and were diving at Garbh Eilean, in the Shiant Islands. It was a short dive for me and Nick as we made the mistake of going straight to 25m and promptly got pulled out to sea by the current. Och well!

We had three dives as we made our way south down Harris – a really fun drift in Scalpay Sound and two 45-minute dives at Rubha Quidnish and Rubha Vallarip, both to around 29m. Large boulders, small lobsters, jewel anemones and big crayfish all caught my eye, while the nudibranch/slug lovers reported an abundance of small life.

St Kilda or bust

All of this was taking us closer to the point where we could make the hoped-for break for St Kilda and make it we did, setting off around breakfast time and arriving in time for a 6pm dive (hoorah for it being late June!).

We managed an overnight stay, two dives the next day and then a sneaky one as we ran back for cover in Harris. A particular regret was that we had to make a choice between diving and going ashore. As a group, we chose diving, but it was a very reluctant choice.

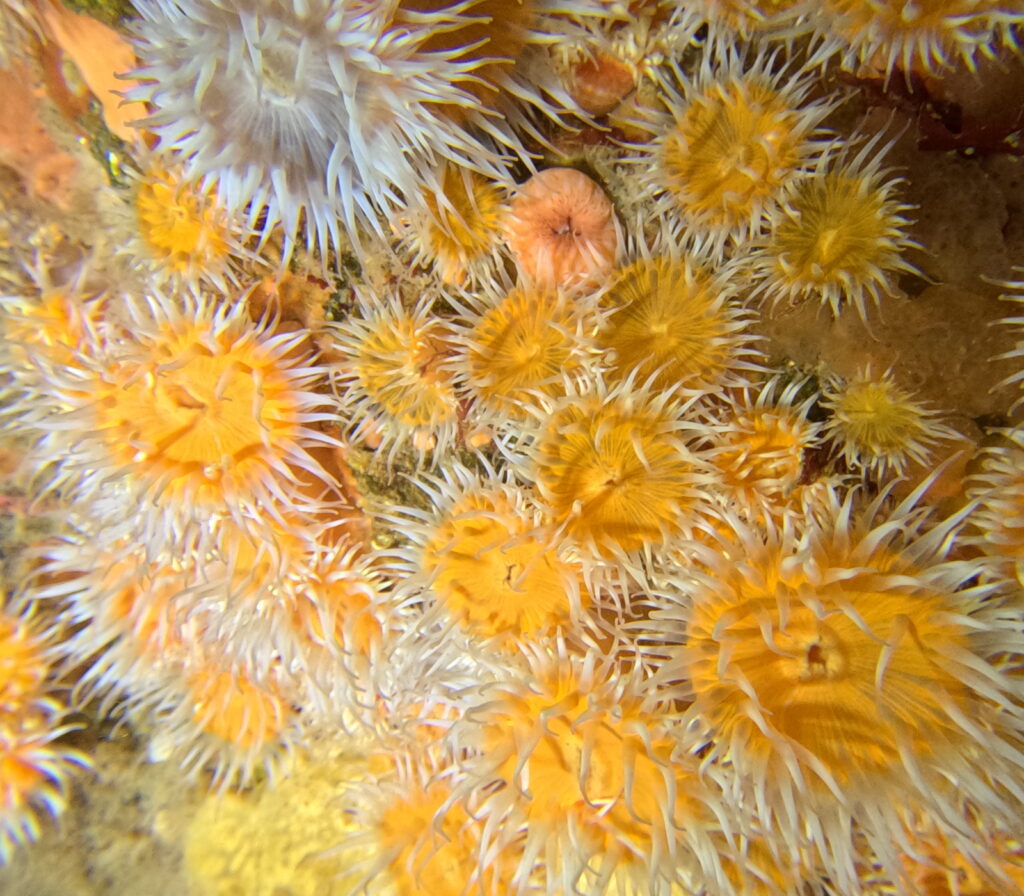

Having experienced very good but not stunning visibility around Gairloch and Harris, our first St Kilda dive, on ‘Bob’s Pinnacle’, was jaw-dropping. Not knowing what to expect, we descended through clear water and sparkling late afternoon sunlight and briefly swam through a kelp forest to be confronted by a sheer wall completely covered in every kind and colour of anemone. [Thanks to Ben Jaffey for these and the other wildlife pics.]

This continued to 26m, where the rock became bare but the visibility and light were still excellent. Nick and I ventured briefly to 40m before zig-zagging our way back up the rock-face, turning back each time we again hit bare rock, the combination of light and current having turned just one face of the pinnacle into a cornucopia of life and colour.

At 8am the next day we were back in the water on Stac Lee, victims of a vague, early morning briefing, poor understanding on our part and a strong current [ see point 5 above]. Sasha and Gabriel swam into the cliff, followed the wall and had an excellent dive. Nick and I – and some of the others – didn’t.

Our third dive, at Sawcut, was a lot better – a massive, anemone-coated cleft in the cliff face – but still a bit frustrating as we tried to identify particular features underwater. Personally, I should have spent less time looking for and more time looking at.

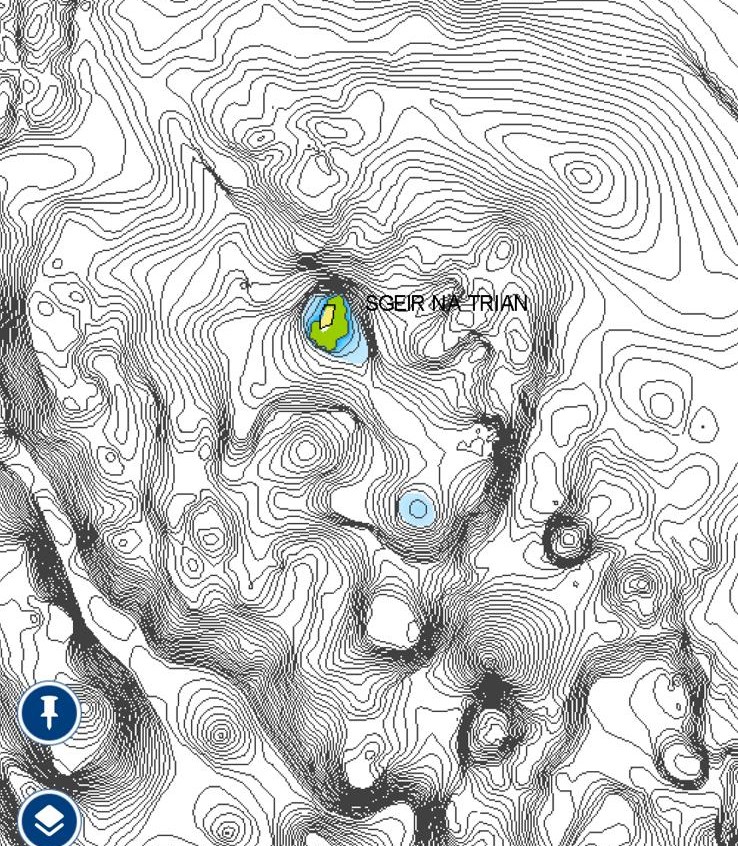

Our final dive before we returned to ‘civilisation’ was at Whale Rock, a huge double pinnacle sitting almost half way between St Kilda and Harris. Finning hard down the shot line in a strong current, my heart sank as I felt the telltale rush of cold water through the open end of my drysuit zip. But Nick managed to close it and thank goodness he did – this one definitely rang all my personal bells!

An enormous underwater landscape opened up below us, with smooth, sheer walls plunging through clear water from 20m to well over 50m. We confined ourselves to 35m and resisted the temptation to cross to a second pinnacle, but still only managed an all-too-short 36 minutes. We wished we could have spent longer in the ‘shallows’ (still 20m!), where forests of huge kelp were interspersed with vertical walls covered in plumose anemones and dead men’s fingers, and rarely seen red blennies grinned at us from inviting cracks in the rock that we longed to explore more fully.

More Hebridean delights

Taransay was the site of both our overnight mooring and the our first dive ‘back’ in the main islands of the Hebrides. Nick and I were on anchor watch that night, a duty shared between us when we were anchored rather than moored. I did the midnight–2am slot, alternating between reading a book, checking the instruments and admiring the midnight sun. The dive there was fun too!

We enjoyed three more typical Hebridean dives, at the Ascrib Islands, Loch Torridon (a pinnacle) and Glas Eilean, by which time I’d got my eye in on the small stuff and was even pointing out nudibranchs to my buddies!

So there you are – a true Hebridean Odyssey. Would I do it again? In a heartbeat! But this time, I’d follow my own top tips.